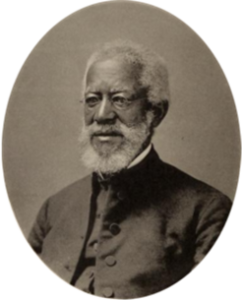

Alexander Crummel (1819-1898)

Alexander Crummel (1819-1898)

Imagine a world where you are seen as an inferior in the land of your birth. Alexander Crummell existed in such a world and had the determination and foresight to try to change it. Alexander Crummell was born in 1819 in New York to Boston Crummell—a former slave—and Charity Hicks, a free black woman. His parents were active

abolitionists

and their home was used to publish the first African American newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, which promoted the abolition of the slave trade; Alexander was strongly encouraged by his father to take part in the struggle for African American rights and as a young boy he would work for the American Anti-Slavery Society, an experience that would shape him for the rest of his life.  Have a go at creating your own short newspaper article based on Freedom’s Journal, telling about what is going on in your local area. Think of a catchy name for your newspaper, and you can even add photos or drawings to illustrate your article.

Have a go at creating your own short newspaper article based on Freedom’s Journal, telling about what is going on in your local area. Think of a catchy name for your newspaper, and you can even add photos or drawings to illustrate your article.

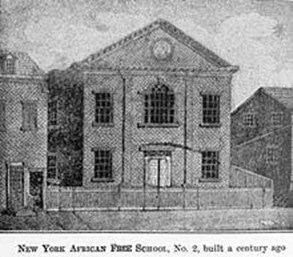

For a free black man of the time, Alexander was well educated and began his formal education at the African Free School in New York alongside other future African American abolitionists James McCune Smith and Henry Highland Garnet. After graduating from the Canal Street High School, Alexander started at Noyes Academy in New Hampshire; however, he wasn’t there for long as the school was soon attacked and destroyed by an angry mob opposed to black students. During his studies at the Oneida Institute in central New York, Alexander realised his calling was to become an Episcopal (Protestant) priest, while his talent as a preacher ensured him a place as a keynote speaker at an anti-slavery convention in 1840.

Lithograph of the African Free School, 1922

Lithograph of the African Free School, 1922

Unable to enter the General Theological Seminary in New York City because of his race, Alexander studied theology in Massachusetts where he was ordained in 1842. He quickly realised that racism within the Episcopal Church hierarchy in America was endemic and in 1847 he travelled to England to raise money for his small congregation at the Church of the Messiah, Providence, Rhode Island. While in England he preached, spoke about abolitionism in the United States and raised nearly $2,000, the equivalent of $64,150 in today’s money. With the sponsorship of the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay and the surgeon Benjamin Brodie he studied at Queen’s College, Cambridge between 1849-1853 and despite the fact that he had to take his final exams twice to receive his degree, he is the first black student officially recorded as having graduated in the university’s history. He lived at 12/13 Botolph Lane while in Cambridge.

President’s Lodge, queen’s College, Cambridge

President’s Lodge, queen’s College, Cambridge

It was while studying at Cambridge that Alexander developed his theory of Pan-Africanism , which became his central belief for the advancement of the African race. He believed that all those of African descent in the Americas, West Indies and Africa should unite as one race; this racial solidarity would therefore—in theory—prevent slavery, discrimination and continued attacks on African people throughout the world. In 1853, Alexander moved to Liberia , a country founded as a colony for free black Americans, to preach his message. As a missionary for the American Episcopal Church he aimed to convert native Africans to Christianity and he encouraged ‘enlightened’ or Christianized ethnic Africans in the United States and the West Indies to go on a civilising mission to make the African continent Christian. Although he was highly successful as a preacher in Liberia, few American blacks were interested in his call to convert native Africans—they were more concerned with the struggle to obtain equal rights in their own country. Furthermore, the indigenous tribes in Liberia such as the Kru and Grebo had little time for African American missionaries who treated their own beliefs as inferior. Ultimately, Alexander’s dream of a united racial and Christian African identity never materialised and he returned to America in 1873. He never stopped working for a better world for black people and he spent the last years of his life founding an academy for African American scholars which opened in 1897. Alexander died a year later in 1898, aged seventy-nine. The great contradiction of Alexander Crummell’s life was that he was a passionate abolitionist and advocator for black rights, but also a supporter of the colonisation of Liberia and the—often forced—conversion of African natives by African Americans. However, he should be remembered for his influence on twentieth-century black nationalists and Pan-Africanists, including Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois, whose ideas helped found the world we know today.