Written by Robin Sterne, Disability Heritage Research Volunteer

Supported by Beau Brannick, Collections Officer at Museum of Cambridge

Warning: This research piece discusses disability history, which includes the use of historic, out-of-date, ableist language.

This research piece was made possible by a two-year initiative and £99,802 grant from the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund through the Museums Association. This ground-breaking project will place disabled individuals at the forefront of researching, curating, and sharing the histories of disabled people in Cambridgeshire.

The Cambridge Union Workhouse Quilt , CAMFK:1.6.95

This object from The Museum of Cambridge’s archives is a patchwork quilt, believed to have been made by disabled occupants of the Mill Road Cambridge Union Workhouse (more modernly known as Ditchburn Place). The quilt itself is made from scrap fabric- likely old bedding, clothes, and dish cloths/ cleaning rags- and is without any wadding or backing. It was donated by Maimie Blow, an attendant who was a staff member at the workhouse from 1927 to 1930.

Workhouses were first introduced in Britain due to the Poor Law Act of 1388 (after the black death, when there were massive labour shortages). The oldest documented example of a workhouse dates to 1652; however, it is believed there were other variations before this. In 1576, the law stipulated that if a person was able and willing, they needed to work in order to receive support. As a result, workhouses gained popularity as they became a way to offer work and shelter to the poor. By the 1830s, most parishes in England had at least one workhouse.

The quilt discussed in this research comes from a workhouse which has been known by many names over the years. The building itself, which was situated on Mill Road, Cambridge, is the oldest surviving building on the street and is still open now as a retirement living home- Ditchburn Place. Prior to this, Ditchburn Place was a maternity hospital, midwifery training school, wartime hospital, and, before 1934, a workhouse. Opening in 1838, the workhouse has been home to many inhabitants, all of whom would have been classed as ‘paupers’- people living below the poverty line. Many of the workhouse occupants were also described as ‘infirm’, a term that, although lacking a solid modern definition, originates from the Latin word ‘infirmus’, meaning weak and feeble. It was likely that this term was used for people who, today, would be described as chronically ill, immunocompromised, and disabled.

The Cambridge Union Workhouse also offered something called ‘tramps cells’ from 1879 onwards. These acted as night shelters for the homeless, who would have to queue for hours before being admitted at 6 pm. Once admitted, they would receive a small piece of soap, nightclothes, a meal, and a bed for the night. However, the next morning, they would have to pay for the previous night through heavy labour for four hours. They then had to move on to the next workhouse as they wouldn’t be permitted to stay more than one night at a time and couldn’t return to the same workhouse ‘Tramp Cells’ until several days had passed.

The Cambridge Union Workhouse was built in 1838 for a whopping £480 (which by today’s rates is roughly £46,411). It housed over 160 inmates at a time, and it is noted that many inmates required ‘strict discipline’, which included whipping and solitary confinement.

Photograph of the Cambridge Union Workhouse, Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:1.24.59

The punishment book, held in the county records office, details the offences and their corresponding punishments. The original layout of the Cambridge Union Workhouse included four courts, each with Porter lodges, tramps’ cells, bedrooms, offices, master’s and matron’s rooms, day rooms, dormitories, baths, workshops, a chapel, and a mortuary. Once the workhouse opened, it was immediately found to be too small for its purpose, as the public demand in Cambridge was too high, and they had to expand.

Inmates were separated into categories, which dictated where they stayed in the workhouse and what they did in their day-to-day. Able-bodied men and boys over 13 would be lumped together and sent to do labour-intensive tasks. Able-bodied women and girls over 16 were also categorised together. Children would be separated from their parents, and when they were over the age of 7, would be segregated by gender. Infants could stay with their mothers until they were deemed old enough to bunk with the other under-7s. Aged and ‘infirm’ men were grouped, the same as aged and ‘infirm’ women. They would spend most of their time in day rooms, as they were either unable to work at all/ or could only perform specific tasks. It was in these day rooms that occupants of the workhouse would look to crafts to while away the hours. It is suspected that this is how the patchwork quilt that remains in the Museum of Cambridge survives to this day.

Maimie Blow

Maimie Blow, the person who donated the quilt, worked at the Cambridge Union Workhouse from 1927 to June 1930. She was described as an ‘Infirm Attendant’, which meant she had regular contact with the disabled and elderly residents.

Photograph of Maimie Blow and residents of the Cambridge Union Workhouse, Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:2.6.95

Alongside the quilt, the Museum of Cambridge holds several photographs of Maime Blow, other attendants, and inmates, as well as a short written history by Blow about her time at the workhouse. In her own words, Blow said, “There were nineteen old ladies to look after… they were nice old ladies”. She also supervised around twenty inmates from the men’s block. In her written history, she details the entertainment they had there at that time, which included concerts, a radiogram, a hall for games and dances in which Cambridge residents from outside the workhouse could join in. Blow also took the women on walks and day trips outside the workhouse, allowing them to experience freedom periodically.

Blow recalls an incident in which they had to quarantine the workhouse; “we had a smallpox casual come in. Reg searched him and I was with Reg so we were not allowed out of the Institution for three weeks”. She says they were all vaccinated (“scarified”) and some of the inhabitants had “bad arms afterwards”. Reginald Turner, who would later become Blow’s husband in June 1930, was the Labour Master at the workhouse and was described by his superior as “an exceptionally good disciplinarian” at the Poor Law institution (the workhouse) during his time there.

On 18th June 1930, the inhabitants of the workhouse all celebrated the newlyweds, and Blow describes how she left her bouquet for the “poor old dears” that she had looked after. She also describes how the ambulatory patients all lined up to wish her and Reginald farewell. After their marriage in 1930, they honeymooned for a week before deciding to settle in the Oundle Union in Northamptonshire until 1933. It was here, at the Public Assistance Union in Irthlingborough, Northamptonshire, that the couple became the youngest Superintendent and Matron in the country.

The Quilt

The Cambridge Union Workhouse Quilt, Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:1.6.95

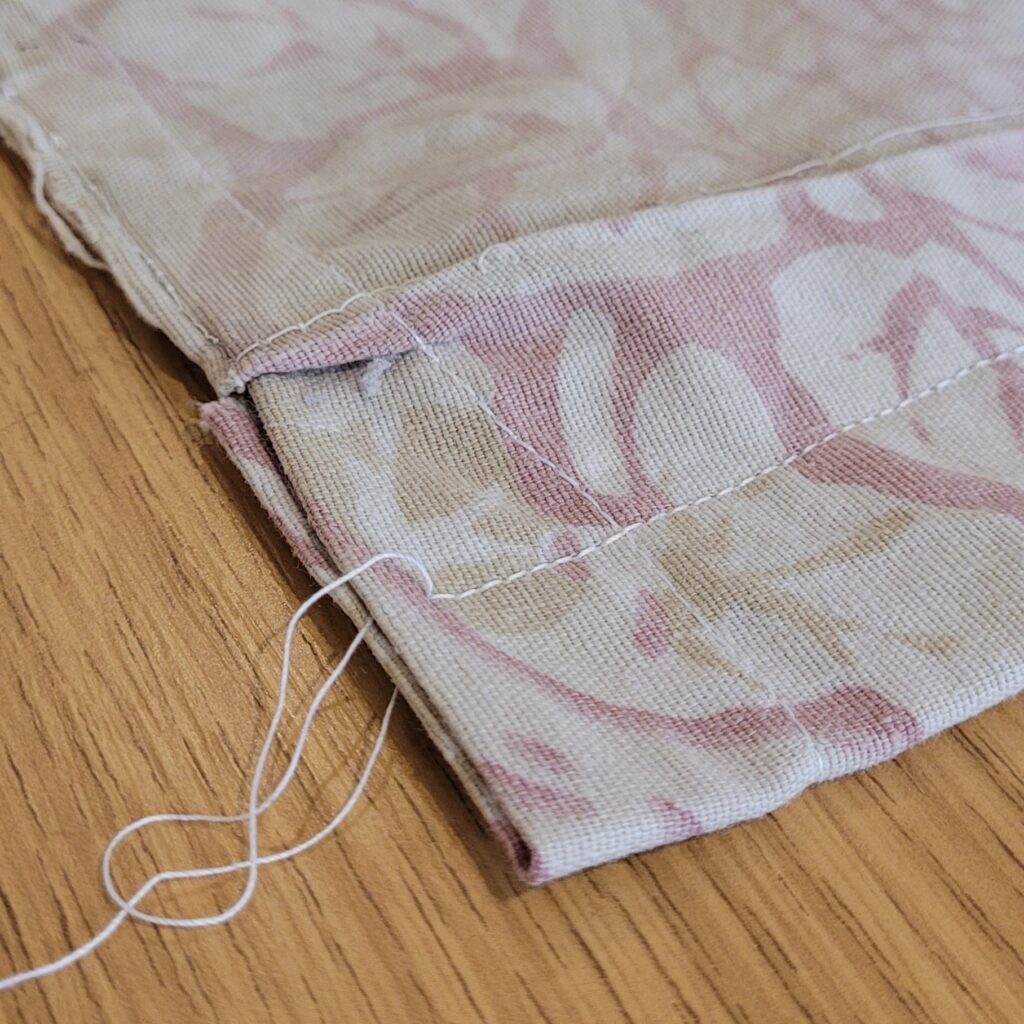

The quilt itself is made from a variety of scrap fabrics, most likely old clothes and bedding, all sewn together in no particular pattern. Near the centre, the design becomes more complex, featuring rectangles and triangles that tessellate in a disorganised pattern. The piece has no wadding or backing, making it very thin and unsuitable for cold nights; however, it might have made a lovely bedspread. The fabrics used in the piece include a denim-like blue material, pink floral cotton, beige/ white fabric, stripey fabric, and a variety of coloured gingham, amongst others.

Due to the organisation of the stitches, the quilt was most likely machine sewn. It is hard to say for sure, but there may have been a workshop of some kind in the workhouse, which included sewing machines for inmates to use in the little free time they were offered. There may have been only one sewing machine brought out into the day room for inmates to use.

The Cambridge Union Workhouse Quilt, Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:1.6.95

Given the nature of a workhouse, a labour-intensive environment, it is likely safe to assume that able-bodied inmates didn’t make the quilt, as they’d spend most of their time working. This suggests that the disabled occupants of the Cambridge Union Workhouse (or the Poor Law Institution, as it was known when the quilt was made) were responsible for the creation of the piece. We can also infer this because Maimie Blow’s role in the workhouse was to look after the elderly and ‘infirm’, and since she donated it, it’s likely there was a direct connection.

When it comes to disability history, a lot is unknown or hidden because in the past, disability was seen as shameful and kept behind closed doors. This was also the case for poor people, which contributed to the growing popularity of workhouses. A workhouse meant that people from lower classes were kept out of view of the public, and would perform hard, strenuous tasks as labour in return. Thanks to Maimie Blow’s donation to the museum, we can see that the lives of disabled workhouse inmates are important and that their stories deserve to be told, even if that may not have been the case for them 100 years ago when the quilt was being made.

Great article!

Thank you for such an interesting article which I found via Facebook. I was fascinated by the origin of some of the pieces of material, the piece with the black stripes reminds me of the uniform worn by Lucy Jolly of Ramsey (1870s) one of the ‘Habitual Criminals’ at Huntingdon goal, that material has wider stripes but the piece in your quilt also has that kind of institutional look about it!