By Dr N Henry

When Roland Parker published his book Town and Gown in 1983, he admitted in his introduction that the relationship between the town of Cambridge and the University was a “delicate topic” and he expressed his anxiety at potentially upsetting the parties involved. Forty two years later, the subject remains sensitive. Tourists who visit Cambridge come to see the world renowned University and the town is often described as a “town within a university”. However this is misleading as the town existed long before the first students arrived here. Local history, just like colonial history, needs to be examined again and again. Lost voices and narratives need to be constantly reclaimed.

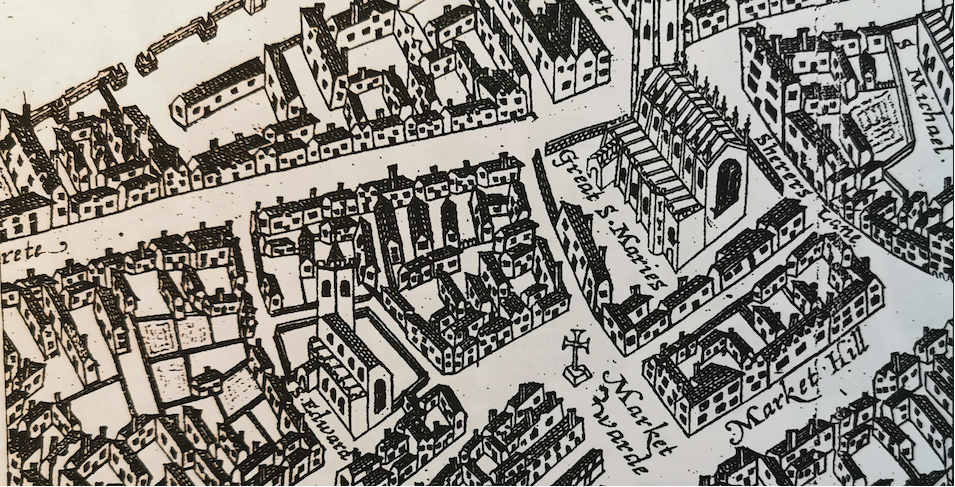

When the first group of students (the scholars) and teachers (the masters) arrived, around the year 1209, they were fleeing troubles with townsmen in Oxford. Their refuge, Cambridge, was a well established and successful market town with a closely knit community that thrived on buying and selling goods carried on a network of natural waterways, the Cam and the Ouse. The town had finally recovered from the Norman invasion and had just received its first royal charter declaring it a free borough with full “liberties and free customs” (Charter of 1207- Cooper vol 1 p.33). The arrival of students was immediately perceived as another arrival of “foreigners” meaning “non-locals”. The young male students were not always well behaved and not always well managed by their masters (the teachers). Soon complaints were sent to the King by both parties, students and town.

Students complained that they were financially taken advantage of by townspeople who, they said, overcharged them for food and lodging. Townspeople complained about the bad behaviour of the young students. King Henry III’s view was that local government (the burgesses) was neglectful in its duties of peace keeping, and thus Henry III empowered the Sheriff of the county to act and protect the scholars from harm (Cooper vol 1 p. 52). In 1270, the King and his son visited the town to act as mediators. The result was a formal agreement that five scholars (students) and ten burgesses (townspeople) should be chosen to “keep the peace and tranquillity of the University” (Cooper ibid). It was clear that royal power favoured the students and their masters. The King viewed the successful creation of a new centre of learning as more important than the lives of the ordinary people of Cambridge.

During the twelfth and thirteenth century universities emerged in France, Italy, Spain and Germany. Knowledge and the cultivation of learning were becoming signs of power. In England, Oxford University was almost the only independent centre of scholarship. Learning usually happened in cathedral or monastic schools under the power of local bishops. The King, unsurprisingly, was very keen to support the foundation of a new university and take it under his own wings. Some students, although not all, belonged to the upper classes of society and probably had close links with the royal household ensuring support from royal power. The King showed great leniency towards the scholars as is shown in the events of 1261 when, following a general affray between university and town, sixteen townsmen were executed and twenty-eight scholars pardoned (Cooper vol 1 p. 48). There was little sympathy for townspeople and even less for the burgesses of the town who were often declared incompetent and negligent by the King in his letters.

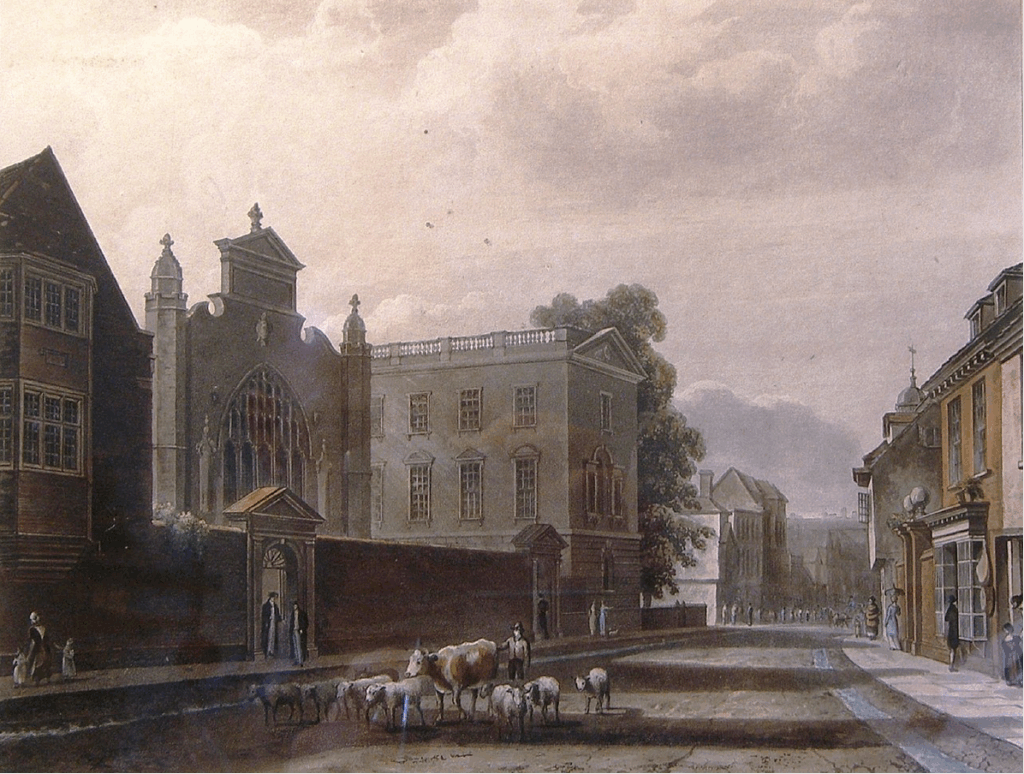

Coexistence between students and townspeople was painful. However, the creation of colleges brought some relief to the situation. Peterhouse was the first college to be founded in 1284. Others appeared gradually over time. The creation of colleges, thanks to land and money donated by rich patrons including the King, meant that students could live a more separate life from the town. They were no longer entirely dependent on unscrupulous landlords. Colleges were, and continued to be, places where students live, study, eat and party. The creation of colleges was a game changer and also provided the University with a physical presence in the centre of town, a presence further extended by the gradual purchase of extra land, town dwellings and shop premises. Even today most small shops in town are in buildings owned by colleges. The Rose Crescent area for example belongs to Gonville and Caius College and is a mix of student rooms and shops that are rented to local businesses.

The creation of colleges marked a change in the economic balance between town and University. However, there remained the issue of food and clothing for which students relied solely on the town. Endless disputes led the King to award the Chancellor of the University the right to sit on tribunals overseeing the trading of bread and beer (Charter of 1268, Cooper vol 1 p. 51). Over time the University gained control over weights and measures, price fixing and the collection of fines from traders. By the seventeenth century the University had even become “clerks to the markets”.

Samuel Newton, a town Alderman (councillor) describes in his diary how the University policed the market:

Entry of 22 October 1664:

Saturday, in the morning about 10 of the clock, Dr Fleetwood, then Vice Chancellor, with the Proctors taxers and some Doctors as the custom yearly is (the University being Clerkes of the market) made proclamation thrice, and caused to be proclaimed the orders and penalties concerning the selling of fish, victuals etc…these proclamations are made in each market. (Newton p.4)

Whilst it seems ridiculous today to imagine Cambridge professors standing in the market looking for rotten fish and other foodstuff unfit for human consumption, the powers granted to the University were of significant economic importance through the control of resources and clearly placed the town in a position of subservience. Samuel Newton’s words “as the custom is” resonate as words of acceptance, his voice reflecting the submission of the town. The University had essentially been awarded manorial type rights, an ancient customary system inherited from feudal times, that granted the Lord of the Manor control over the regulation of the trading of essentials, the right to punish and help keep the peace (Rigby p.27).

In 1605, in an attempt to regain control over their affairs, townspeople had asked the King for a new charter to reaffirm their independence as a free borough. The charter did confirm that the town should enjoy “all the liberties of a free borough” but an additional phrase stating that “nothing in the Charter should prejudice or impede the privileges of the Universities” rendered the Charter meaningless. It was just a “very expensive piece of parchment” as Roland Parker writes (Parker p. 121). In theory the town was free but in practice it had lost most of its agency to the “Lord of the Manor”, the University of Cambridge.

References:

C H Cooper, Annals of Cambridge, volume 1, 1842

C H Cooper, Annals of Cambridge, volume 3, 1845 (see p. 17 for the Charter of 1605)

S Newton, Diary (1662-1717), edited by J E Foster, 1890

R Parker, Town and Gown, Cambridge, 1983

S H Rigby, English Society in the Later Middle Ages, MacMillan Press, 1995