“The range of clay pipes found (in Cambridge) provides a complete history of clay pipe manufacture.”

Recent archaeology reinforces the importance of social history finds and their interesting backstories – of places and their inhabitants. Clay tobacco pipes are commonly dug up in back gardens, old rubbish dumps and municipal flower beds across the country. Apart from making interesting diversions for gardeners, they also make excellent date indicators in post-medieval archeological sites because their design and process of manufacture has gone through gradual yet distinctive changes over time, making them easily datable. Cambridge is an exceptional hotspot for these curiosities and because of its location and early international trade, by both road and river, the range of clay pipes found here provides a complete history of clay pipe manufacture.

Sir Walter Raleigh is often credited with introducing tobacco to Britain, but early sailors and traders first brought it to these shores in the 1550s. However, Raleigh did help popularise smoking at the court of Queen Elizabeth I. At first, tobacco was expensive and the province of the well-to-do. The Cambridge finds suggest that the ‘town’ of the sixteenth century had a population of affluent locals and newcomers, students and traders, who embraced the smoking habit at an early stage. One of the earliest pipes ever found in the country was discovered at the back of the colleges in St John’s Wilderness.

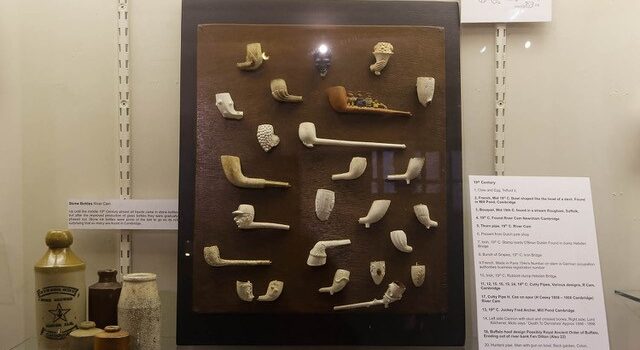

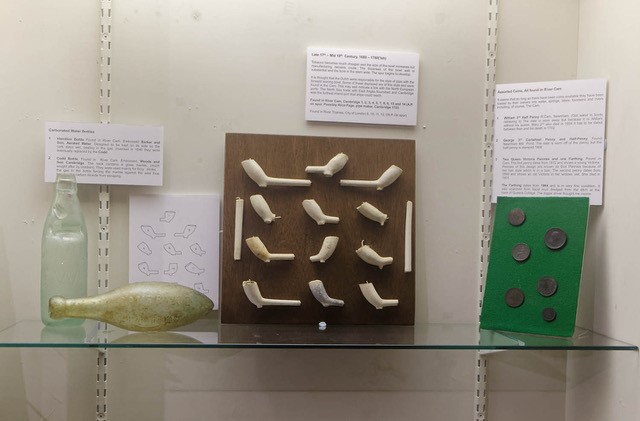

Over the years the Museum of Cambridge has accumulated a large collection of pipes of all shapes, sizes and constructions. Some are on permanent display and many others are stored behind the scenes. Although the sites of many of the finds remain unattributed, two predominant sources have been identified. Before 20th century building, the countryside area around the Barton Road was covered with gravel pits that were later used to dump the town’s rubbish. The second, our very own linear rubbish pit, better known as the River Cam, gives us a full, if jumbled, history of clay pipe manufacture. This history was illustrated by John Clements in his 2018 exhibition of ‘Finds from the River’.

The people of Cambridge have thrown and dropped huge numbers of pipes into the Cam over the centuries with supply being supplemented by the international shipping trade (the town being an important port until the arrival of the railways) and many foreign pipes, particularly from Northern Europe, that have found their way onto its muddy bottom.

In 1914 – 16 a collection of fifty clay tobacco pipe bowls and a clay wig curler were among the finds at the site of Bredon House on Barton Road, Cambridge. This house was built in 1914 for John Stanley Gardiner (1872-1946), Professor of Zoology, and Edith Gertrude Gardiner (nee Willcock, 1879-1953), a biochemist, who lived there with their two daughters, Nancy (1911-c.1955) and Joyce (1913-1994) until after WW2. From 1965 it became part of Wolfson College. Around the same time an amateur archaeologist, Hugh Scott (entomologist, biogeographer and then curator of the Museum of Zoology), moved into a new build in Millington Road and found a large number of clay pipes and some clay wig curlers in his garden topsoiI. He was given further finds from a nearby large plot by the boys of Littleton House, a school for mentally disadvantaged boys, which was supported by the scientific instrument maker Horace Darwin. In all, 180 pipes formed his collection, from 1.25 acres.

In 1916, Scott combined both sets of findings in a paper to the Cambridge Antiquarian Society which was published the following year (Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society Volume 20 (1917)). Catherine Parsons, one of the founders of the Cambridge Folk Museum, now the Museum of Cambridge, was on the Society’s committee at that time. She was a prolific collector, writer and contributor to the Society and to the Museum. In 1937 she donated 143 of the objects from her collection of Cambridgeshire ‘bygones’, but as far as we know there were no clay pipes!

In his paper, Scott seems to confirm that the sites at which the pipes were found were refuse dumps. Certainly, other finds, including teeth of domestic animals, supported his premise. The majority of the pipes were also in poor condition and it is known that pipes were often considered objects of single use by the rich and also that it was bad luck to throw away an unbroken pipe. The poor would smoke until their pipes fell apart or the stems were blocked. Often, people would shorten the pipe stems to make them useable for longer.

Because of the high price of tobacco, pipe bowls in the ‘early’ phase of smoking (1580-1660) were small and well-made, but, as the price of tobacco dropped, the bowls increased in size and quality deteriorated, the pipes developing large heavy stems and bowls. However, over time, manufacturing processes continued to improve while tobacco became cheaper. By the late 18th century, novelty bowls were being produced complete with moulded designs of popular celebrities and politicians, commemorative events and advertising wording. The artistic pipes reached their peak by the latter half of the 19th century before they fell out of favour, being replaced by wooden pipes, cigarettes and cigars.

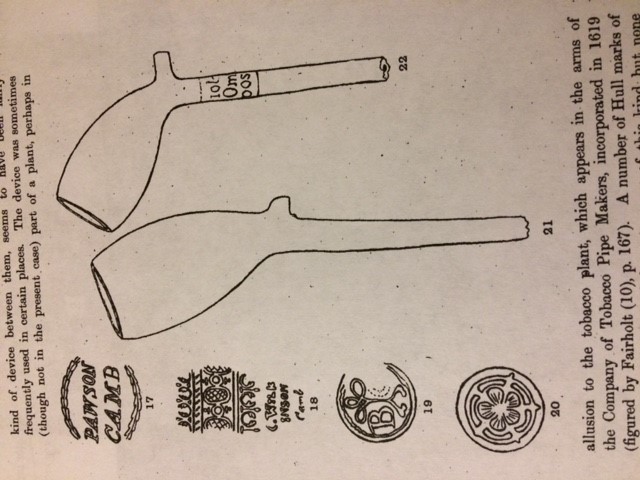

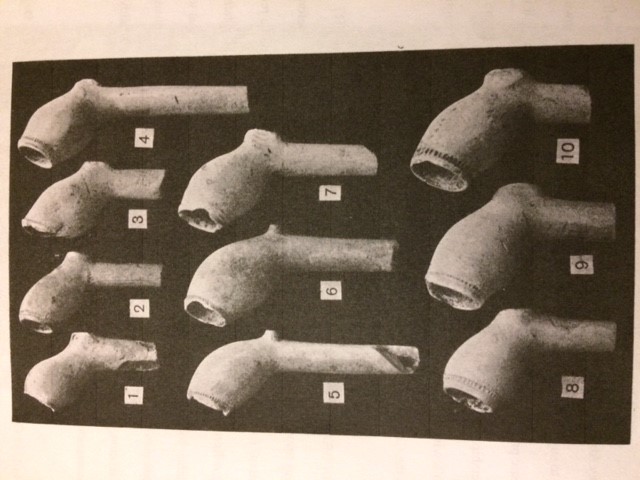

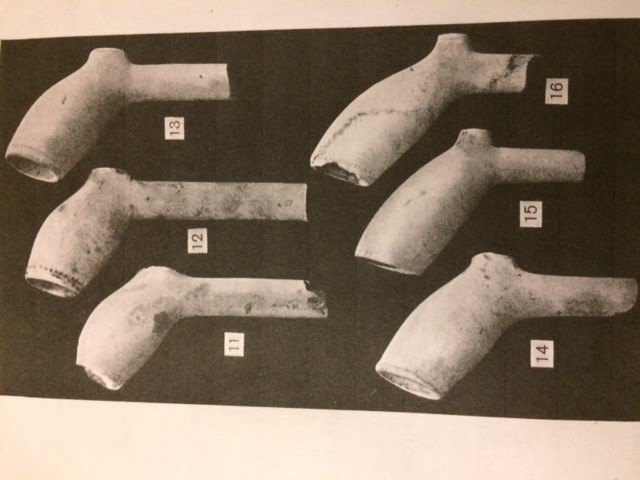

Scott assessed the possible age of his collections together with their origins and possible makers. He concluded that the majority of his pipes were 17th century. The two collections (Bredon House and Millington Road) form an interesting series to illustrate the change in shape of the pipe bowl and heel over time and 16 have also been illustrated. In Scott’s comparison, he suggests that pipes 1-4 can be attributed to the late 16th or early part of the 17th century. A pipe much like that of 7 was found in an old house in Crooked Lane, London after the Great Fire of 1666. Pipes 8 -10 show an enlargement of the bowl which indicates a likely later date. Interestingly, the pronounced heel shapes of pipes 5 and 6 match those from people who died of plague in London in 1665 when smoking was much practised as a means of warding off infection. Some scholars suggest that these might be Dutch in origin, and certainly pipes attributed to the Dutch have been found in Cambridge.

Only 2 of Scott’s collection (pipes 3 and 11) bear a maker’s mark. He only managed to identify one local maker, ‘Pawson’, who was connected with 11, Sidney Street in Cambridge. Pipes 11-13 show further evolution of form and are characterised by big flat heels. Several of this transitional type were discovered at St John’s College in 1881 and were attributed to the early part of Charles II’s reign. Pipe 14 is of the Dutch type associated with William and Mary c.1690s. Pipes 15 and 16 belong to the 18th century.

The photographs illustrate John with the exhibit ‘Finds from the River’ of 2018. The three boards show the pipes (mostly found from the Cam when it had been drained). There are small bowls from around 1600-1680, larger ones from 1680 to the mid-eighteenth century and a mixed collection from the 18th century to the end of the Victorian era.

Next time the river level is lowered for building or bank work or if you see a freshly dug flower bed go and have a rummage. You never know what you may find.

Images copyright Peter Nixon.

This post was written by Carolyn Ferguson and John Clements, both volunteers at the Museum of Cambridge.