Over the Summer Holidays, we’ve been learning more about some of the endangered crafts from the history of Cambridgeshire and the wider region. Our Engagement and Learning Officer, Alex, has been digging into the history of these crafts and has some interesting facts to share with you all.

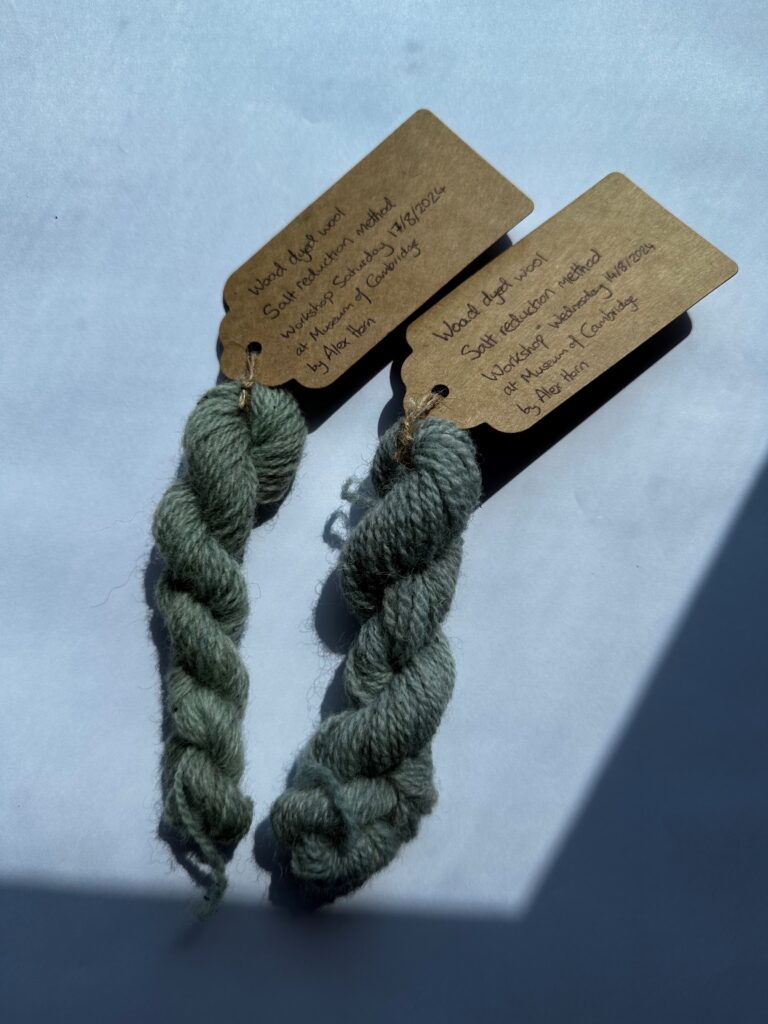

Natural Dyeing with Woad

First off, due to the success of Woad-Working Wonders last Summer, we’re back with natural dyes. Woad has been used to produce a natural blue dye for thousands of years, the ancient Celts of pre-Roman Britain used it to produce body paint to cover themselves when going into battle. It is thought that this might be due to the antiseptic properties of the woad, such that if a warrior was wounded in battle, the presence of the paint would help prevent infection.

Cambridgeshire is steeped in woad history, too. Not only was the southern border of the Iceni tribe lands just outside the Museum of Cambridge on the river Cam, from where Boudicca launched her revolt, but even in more recent times, the region has been important to woad growth.

Woad is a very nutrient-thirsty plant, so farmers have to constantly move around to keep growing. When they did that, they also moved the mill that processed the woad into usable dyestuff. The last portable woad mill in Europe was in Parsons Drive, near Wisbech in Cambridgeshire. It came to rest there and ceased operation in 1914, by which time synthetic dye was much more readily available.

Now, woad is used more by hobby dyers and specialists, and we’re trying to keep that legacy alive with Woad-Working Wonders.

Fan Making

As part of the Lost Craft Drop-in activity, we will be designing our own paper fans. Arising in popularity in the 17th century, when the building the Museum of Cambridge occupied would have been bustling as the White Horse Inn, fan making is now a critically endangered craft. Only one person is registered as receiving their main income from fan making in the entire country.

Nowadays, the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers continues to advocate for this lost art, with courses and philanthropy to keep it going for years to come.

Fixed fans have been around millennia, but the folding fan that we know today – as popularised perhaps by Regency dramas like Bridgerton and Pride and Prejudice – became ubiquitous by the early 1700s. With versions like the brisé (with only sticks and no leaf), and cockade (which opens all the way around like a lollipop), there has been some development of style, but ultimately the craft remains fundamentally unchanged for over 300 years.

Marionette Making

String puppets trace back thousands of years, and there is evidence of puppetry in the UK from the 1400s, especially from travelling Italian performers. By the Victorian period, marionettes were popular with adults and children, with puppet theatres cropping up all over the country. They did not last long, and by the 1860s, traveling shows became more common.

One such local traveling show wrought tragedy in Cambridgeshire in 1727. When passing through the village of Burwell, puppet maker and performer Richard Shepherd rented a barn to perform a show inside. Word spread quickly and huge crowds began to amass at the farm. The barn could only accommodate about 140 people, and more and more pushed around outside seeking entry. One such man desperate to get in was Richard Whitaker, who insisted he ought to be let in as he worked for the farmer who owned the barn.

The crowd got so large that organisers nailed the doors shut so no more people could cram inside, shutting the spectators in. At this point, Whitaker climbed up to the hayloft with a torch to light his way. The dry hay caught fire and quickly burned the whole roof of the barn. Spectators tried to escape but couldn’t get through the now nailed closed door. In the end, 85 people died that night, and Whitaker was arrested.

Hopefully our marionettes will be a little cheerier at the Museum!

Hat Plaiting

The beautiful braids of straw hats have a local history link, as this part of the country was perfect for growing the flexible, strong crops that were used for hundreds of years. Most notably, a little way south is Luton – world famous in its time for millinery. Neighbouring town Dunstable was similarly hat mad (quite appropriately) and lent its name to a particular style of plait with seven pieces intertwining.

But sourcing the wheat, milliners came north to the fens, where flat, well-irrigated soil was plentiful following the draining of the fenland. Market sellers in Cambridge sold the raw materials to the hatmakers of the 18th and 19th centuries. These were cut to length, soaked and then hand plaited into long bands, which got stitched together to form the bonnets that fashionable ladies of the Victorian era would wear to church.

It takes about twenty yards of plait to make one hat, and even more straw to make the plait, so it was an expensive and labour intensive job. The advent of machine sewing made this somewhat simpler, but hats also began to become less popular. One theory states that the popularity of the car truly meant that hats went out of fashion, as ladies could not fit inside the cars with their big extravagant hats on, so they were removed and ultimately left behind.

Bobbin lace

Overwhelming to look at, bobbin lace making is a delicate and quite therapeutic skill to learn. Working with pairs of bobbins to knot together very fine thread, the weaver makes intricate patterns which have been used for centuries as trim or decoration. It is now an endangered craft, due mostly to the ageing practitioners of this art.

While it might look impossible to approach, the actual craft comes along nicely, working with only two pairs of bobbins at a time. So even if there are hundreds of threads hanging from the pillow, a crafter only works with a few at a time.

The Museum of Cambridge has lots of bobbin lace in its social history collection, with a beautiful example on display in the Dining Room of the Museum, showing a piece in progress.

There’s been so much discovery throughout the process of putting on the Summer of Making, and we hope that you have been inspired to learn more about the heritage of crafting and maybe even try some of these crafts yourselves!