By Dr N Henry

The charter of 1561, in the reign of Elizabeth I, is an essential document to understand the difficult relationship between Town and Gown up to the nineteenth century. The privileges of the University (its legal jurisdiction over the town) were confirmed and reinforced by royal power, leaving the town itself powerless, but still fighting with the greatest determination for its freedom.

The charter was granted after the receipt by the Queen of a complaint by the University that the town, namely, the Mayor and the keeper of the town prison, had refused to admit to the prison some “delinquents” arrested by the University Proctors. The town had even delivered from prison some people previously committed there by the University. Town and Gown were fighting over the policing and control of these persons.

There was no organised police force in England until the nineteenth century. The policing of a town was done by unpaid constables and volunteers who also acted as watchmen at night to keep the town safe. Policing was very much community based and ordinary people could arrest and present criminals to the sheriff for trial and punishment. The University, on the other hand, relied on the Proctors (originally called Rectors) to ensure peace and tranquility (Cooper vol 1 p.55). The appointment of Proctors is attested in a University statute dating from 1275 and indicating that Proctors had the right to police the town as well as the University. Shared peace-keeping between the University and the town had been granted very early on by royal power but had immediately become the source of tensions; townspeople resented the power granted to a group of non-locals over their personal freedom.

The Charter of 1561 would have been especially upsetting for the town as it reaffirms and reinforces the right of the University to search “by day and by night”, “in the town and suburb, and in Barnwell and Sturbridge” for anyone suspected of virtually anything, both men and women. The University was granted the right to “imprison” at its own discretion, as well as the right to reclaim any member of the University that might have been apprehended by the town and accused of a crime. The Charter explains that such members of the University should be handed back to the steward of the University and if not, the town should be fined £200 for refusal to comply (Cooper, vol 2 p. 168).

The same Charter reinforced the control of essentials by the University, victuals sold at markets and fairs within a five miles radius. The right of the University to collect fines for the unlawful sales of corrupt goods and other manorial type rights were confirmed.

The control of essentials was difficult enough to bear for a community of merchants and traders who had built their town around the fair exchange of goods, but the control of persons was even more painful as the town felt it as a complete loss of freedom. When in November 1601 the University obtained the lease of the town gaol, a very angry town sued the University and, being able to prove continued possession from the time of Henry III, won the case in 1607. However the University Proctors continued to enjoy the same right to search, arrest townspeople and send them to jail (Cooper vol 3. p.27).

The reign of Queen Elizabeth I is a period of intense tensions between town and University. As the privileges of the University increased through royal support, the town reacted and tried to defend its freedom using lawyers and well-connected members of the nobility such as the Duke of Norfolk to represent its interests. However, no effort could beat the Queen’s determination to put the University first as she saw it as an essential instrument of power. This is clearly shown in the farewell speech she gave to the students at the end of her visit to Cambridge in 1564:

This one thing then I would have you all remember, that there will be no directer, no fitter course, either to make your fortunes, or to procure the favour of your prince, than, as you have begun, to ply your studies diligently (Cooper, vol 2, p.202)

Knowledge was seen by royal power as a tool to “support and strengthen political power” (Curtis p.6). University men were encouraged to put their knowledge in the service of the Church and the State. Under Elizabeth I, University of Cambridge became very popular with the gentry and the nobility as the main route to high roles in government. There was a rapid rise in enrolment at the higher levels of society. This contrasts with the more modest background of the earlier students who were often from less well-off families, or were the second or third sons of rich families and, as such, would not inherit the family estate but were destined to serve the Church. This new kind of rich student wore silk and ostentatious ruffs which led the Chancellor of the University to publish decrees, such as that of 1578, condemning displays of wealth and encouraging more modest clothing (Cooper, vol 2, p.360).

It seems likely that the costly outfits of the students would have further contributed to the resentment of townspeople whose ordinary lives had been impacted by the privileges granted to the University by royal power. Their lives had been sacrificed for what the Queen saw as a greater good: acquisition of knowledge and the training of men who were destined to manage the practical affairs of the nation. Elizabeth had clearly defined the role of Cambridge University and its place in English society, presenting the University as a tool for social mobility, at least for the wealthy.

The story of Town and Gown is one of a clash of culture between a community of often rich and mobile individuals looking for social promotion based on their intellectual merits, and a traditional community, the town, based on kinship and close long established local relationships rooted in the fair exchange of goods. The story of this community fell into oblivion as the University produced scientists and politicians who transformed English society and brought “progress and knowledge”. The voice of the town became lost and would have remained so without the efforts of Charles Henry Cooper, coroner and town clerk of Cambridge, who spent many years of his life collecting and transcribing documents in his Annals, recording the desperate efforts of Cambridge people to recover their freedom. A document dating from 1596 is of particular interest as it shows the complaints of the town against the University regarding many aspects of every day life (Cooper vol 2, pp. 548-556). We learn of houses being broken into by students and Proctors entering townsmen’s houses by force in the middle of the night, holding swords in their hands and terrorising a man and his wife fast asleep in their bed. Most of all, there are many complaints about Proctors stopping townsmen from freely trading their goods such as the story of John Barber, a candle merchant, whose encounter with the Proctors is described in the document of 1596:

John Barber, chandler, was with force assaulted at Gog Magog hills by two of the Proctors men, and his horse, his panniers, and a hundred pounds of candle before day taken from him with violence and brought to Cambridge, and then the candles taken away by the Proctors, who threatened him daily to have him vj (refers to an article of law) for carrying the candles out of the town. (Cooper, vol 2. p. 551)

The University, as guardian of “essentials” and overseer of trade, had enforced an article of law that prevented candles to be carried “abrode,” meaning outside of the town. The University, in its reply to the complaint, explained that this was to prevent the impoverishment of scholars (students) as well as artificers in town (resellers of candles).

The voice of the town heard in the document of 1596 is one of outrage at being denied the freedom of trade on which the town had built its prosperity before the arrival of the University. The control of goods, which the University presented as necessary for the benefit of all, was viewed by the town as an abuse of power but, to every complaint, the University was able to match an article of law supporting its legal privileges in the matter.

In a paper submitted to support the application by the University to have Justices of the Peace of their own as well as MPs, University officials even claim that “the inhabitants within five miles have great benefits by the privileges of the University, but retort no benefit” (Cooper, vol 2, p. 435). Whilst the town denounces the University’s abuses of power, the University in turn denounces the town’s lack of gratitude. The same attitude or mentality is displayed by Thomas Fuller in his History of the University of Cambridge, written in the middle of the seventeenth century.

Fuller, who had been a student of the University and later became curate of Saint Bene’t’s Church (1630-3) portrays the resistance of the town to the privileges of the University as “insolence” and writes that “although particular scholars might owe money to particular townsmen, yet the whole town owes its well being to the University” (Fuller p. 179). He also views the freeing of prisoners from the jail by townspeople as “encouragement of all viciousness”.

The study of Town and Gown cannot be undertaken without close attention to the history of mentalities. Conflicting views on the trading of goods and the University’s sense of entitlement supported by royal power, led to a deep resentment from both parties. There was not much the town could do to fight against the privileges of the University. Acts of resistance however did continue in the form of law suits, refusals to let rooms in town to scholars and their servants, and even protesting by denying the Vice Chancellor of the University basic hospitality at the Town Hall as recalled in the diary of Samuel Newton, Alderman of the town in 1669:

…the Vice Chancellor […] with some doctors and the Proctors swore the Mayor not to infringe the lawful liberties of the University, then the Vice Chancellor and co departed without any invitation or so much as a glass of wine… (Newton p.52)

From the year 1316 every newly elected Mayor of Cambridge had to swear to maintain the “liberties and customs of the University”, meaning its legal privileges over the town. This led to many disputes with some mayors categorically refusing to do so at their own expense, and others, like here, finding more subtle ways to condemn the practice by not inviting the Vice Chancellor to the drinks and dinner that followed the installation of a new Mayor. Alderman Newton seemed to have enjoyed recording this small act of resistance in his diary!

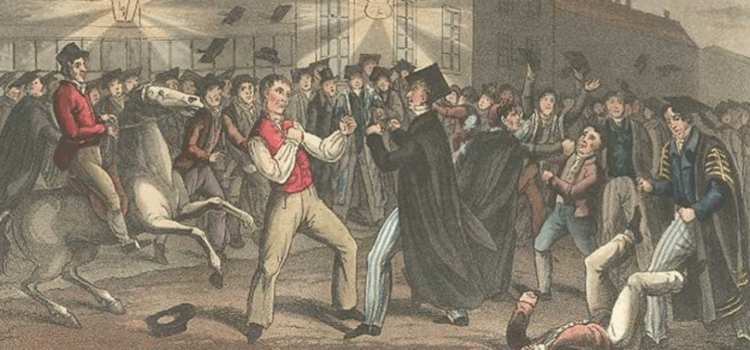

The division between Town and Gown is a very deep-rooted one that cannot be reduced to a simple punch-up between townsmen and gownsmen as portrayed in nineteenth and early twentieth century cartoons. It is the result of a fundamental clash of cultures together with what Geertz refers to as the “hard surfaces of life”, “the political, economic, stratificatory realities within which men are everywhere contained and the biological and physical necessities on which those surfaces rest” (Geertz p.30).

REFERENCES:

Cooper, Charles Henry, Annals of Cambridge, vol 1, Cambridge, 1842

Cooper, Charles Henry, Annals of Cambridge, vol 2, Cambridge, 1843

Curtis Mark, Oxford and Cambridge in Transition 1558-1642, Oxford, 1959

Fuller Thomas, The History of the University of Cambridge, London, 1840 (ed James Nichols)

Geertz Clifford, The Interpretation of Cultures, New York, 1973

Newton Samuel, Diary 1662-1717, ed Foster, 1890