Dr N Henry

The road to the Cambridge University Corporation Act of 1894 that stripped the University of any jurisdiction over the town, was long and torturous. It seems extraordinary that the University managed to keep feudal-type rights over the inhabitants of Cambridge until well after the decline of the manorial system in England. However, factors such as the spacial organisation of the town and the organisational superiority of the University seem to have held the key to the longevity of the dominance of Gown over Town.

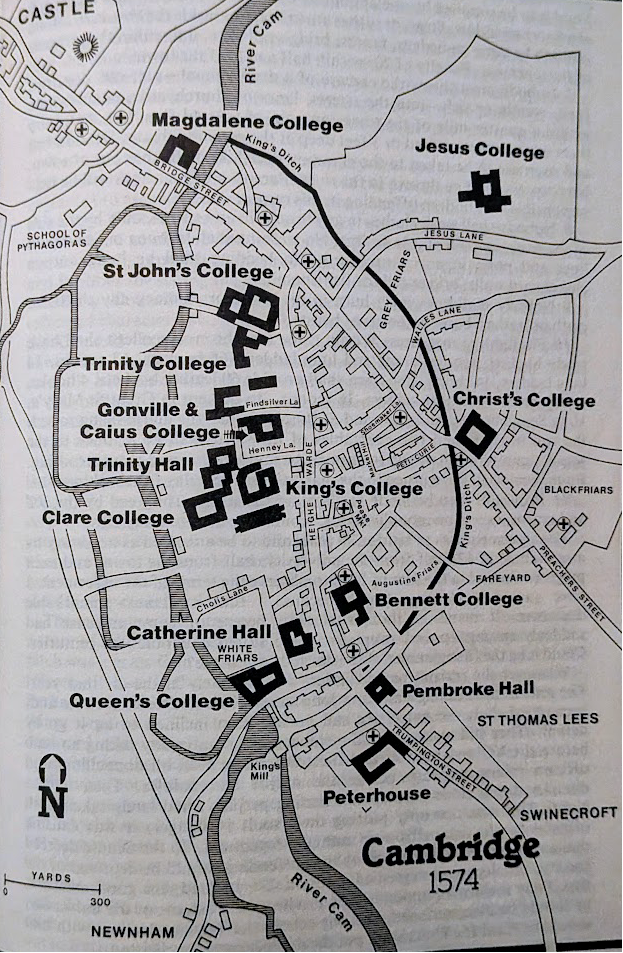

Richard Lyne’s map of Cambridge in 1574 shows how the town’s space was reorganised after the settlement of the University colleges. Commenting on this map Rowland Parker writes:

What it shows most clearly is the takeover by the University of virtually the whole of the western half of the town, with important acquisitions outside the original town limits. […] the town itself was becoming more and more cramped and compressed, yet still practically no expansion was attempted. (Parker p.96)

One of the reasons for the longevity of the privileges of the University is without doubt the organisation of space. Just as manors, monasteries and cathedrals were the strong points anchoring networks of roads and lanes in the Middle Ages, the colleges reshaped the space within the town of Cambridge by establishing themselves all around the market and along the river where resources were traded and transported. While most colleges settled on the western side of the market, enjoying access to the river, on the eastern side, Christ’s College, Jesus College and Magdalene College completed the encirclement of market square. It seems that the University had reorganised the space to fit the specific requirements of its members: easy access to food, clothing (the market and the shops) and transport (the Cam). The town was becoming more and more cramped because the organic growth of the town (from market square outwards) had been impeded by the construction of colleges all around its very centre.

The space of the town was completely reshaped by the University that operated as a social superstructure; space was the “precondition” and a “result” of this superstructure (Lefebvre p.85). It is impossible to understand the Town and Gown relationship without examining the space within which it unfolds. Henri Lefebvre study on The Production of Space and his portrayal of spaces “governed by conflicts and contradictions” seems very pertinent here:

Social relations, which are concrete abstractions, have no real existence save in and through space. Their underpinning is spatial. In each particular case, the connection between this underpinning and the relations it supports calls for analysis. Such analysis must imply and explain a genesis and constitute a critique of those institutions […] that have transformed the space under consideration. (Lefebvre p.404)

The establishment of colleges along the river did transform the space in a negative way for the town as the colleges did not allow tow horses on their banks. As a result, corn merchants found it more difficult to carry grain on the river to the very important Bishop’s Mill and King’s Mill that played such an important role in the production of food. After the construction of the colleges, horses had to walk in the water to tow barges to the mills, making life more difficult for the workers. The colleges effectively privatised parts of the banks of the Cam, establishing themselves as a new power over what had previously been a communal facility.

Authority and power are very much linked to the production of food, especially in the Middle Ages. Although the town could no longer use the banks of the Cam within the property of colleges, the town did however have control of the mills. In 1507 the town had obtained a long lease for the Bishop’s Mill, and the King’s Mill had long been under the control of the corporation of Cambridge. Interestingly, in 1506 Caius College managed to secure the ownership of Newnham Mill further along the river. The efficient functioning of the mills depended on access to the waterways from Quayside (near Magdalene College) where corn arrived on bigger boats and was then unloaded unto barges. Food security for both University and town depended on a certain level of cooperation and a sharing of space (the Cam) that brought with it the tensions and conflicts mentioned by Henri Lefebvre.

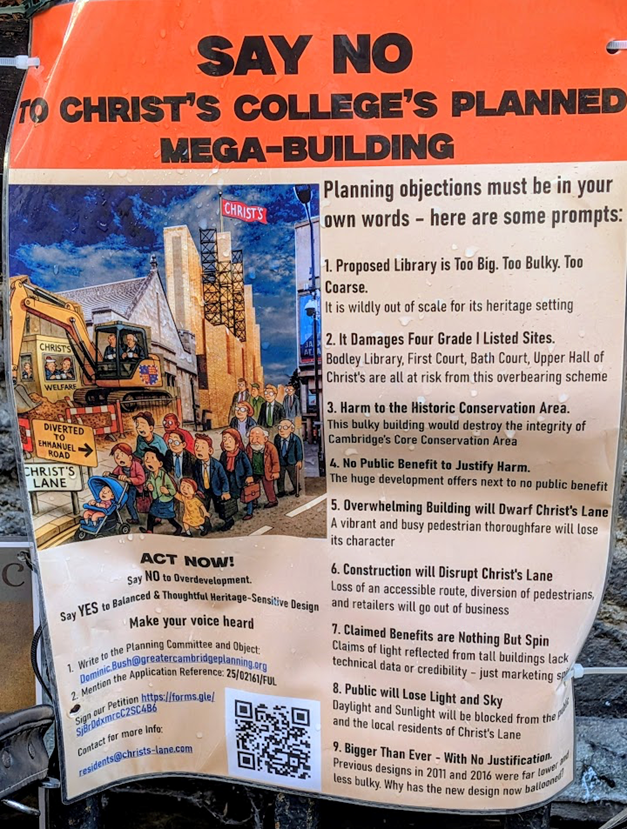

For the ordinary inhabitant of Cambridge the building of colleges along the Cam meant a loss of freedom of circulation as direct access to the Cam from the market square was now made more difficult. The people of Cambridge had to walk around the constraints created by the building of imposing dwellings and palatial courts. Access to the river today remains through hidden narrow lanes like Garret Hostel Lane or King’s Lane. Residents often complain about the detours they have to take to reach Grange Road from the city centre, the colleges operating as a wall between the market and the town, especially as residents are not allowed to take shortcuts through the colleges unless they can show a University card of some sort. Only “members” can walk through the colleges.

The dominant architecture of the colleges remains a subject of tensions between Town and Gown. In 2025 townspeople launched a campaign against the proposal by Christ’s College to build a new library alongside Christ’s Lane, a relatively narrow lane used by locals to reach the Drummer Street bus station and the Grafton shopping centre. Protesters have described the new proposed library as an overbearing building, out of scales and “fortress like”. They also object to the college blocking part of Christ’s Lane during the construction work. The college’s main argument in defence of the project is centred around the concept of “accessibility” of the building for the less mobile members of its community. The townspeople’s argument is that of accessibility for locals to the north of the city.

The dispute shows that space, historically at the heart of the disputes between Town and Gown, remains a crucial issue. The reorganisation of space that took place when the colleges were built, is a permanent legacy that has transformed a successful and free medieval trading town into a “town within a university”. This legacy of the past allowed the University to preserve its privileges well into the nineteenth century and probably beyond, as the colleges own many town houses and continue to acquire more, with for example Pembroke college recently being given permission to turn a Grade two listed former townhouse into student accommodation (BBC online 8 December 2025).

The University exercised its privileges within a space, not only defined by the architecture and location of the colleges, but also within a space that was precisely defined in terms of geographical miles, and continued to expand over time. Under Edward II (14th century) the University jurisdiction over resources and persons is vaguely defined as applying to “town and suburbs” in royal documents (Cooper vol 1 p.76 year 1317). Under Henry VI this space is defined as ‘four miles circumjacent’ from the University (Cooper vol 1 p.209 year 1459) before being extended to five miles under Elizabeth I (Charter of 1561, Cooper vol 2 p. 167). This meant that any victual bought in town, in Barnwell or the Stourbridge fair, could not be taken outside the five miles perimeter without a licence from the University Chancellor.

Licences were to be paid to the University as shown in the articles of complaints against the University drawn in 1596 (Cooper vol 2 pp.548-556). This document contains a list of people caught carrying or selling various items without a licence: candles, wine, meat, kitchen wares, wheat. The town’s outrage at the poor treatment received by these people at the hands of the Proctors is clearly expressed. The complaints especially point out the violence involved. People are assaulted, restrained by force, their horses are killed and their goods taken by University Proctors armed with swords. Both roads and the River Cam were under surveillance. Lighters (small boats) were searched for goods. The five miles that applied to the jurisdiction of the University was a vast circle and it is likely that many did manage to escape from the handful of Proctors that policed this area. Even within a space dominated by the University, traders might have managed to navigate the constraints imposed by exploiting gaps in the surveillance and using their local knowledge.

In conclusion, it seems essential to recognise the importance of the fight for space in the Town and Gown conflict. The reorganisation of the physical space allowed the University to impose itself as a physical authority, encircling the very heart of the town therefore making the surveillance of persons easier for the Proctors. The latter constituted an early organised police force before the town acquired its own in 1836. The organisational strength of the University, visible in its structured courtyards, its imposing architecture and its ability to enforce rules (licensing of goods) is characteristic of dominant groups and an important reason why Cambridge rapidly lost its freedom and became a town within a University.

REFERENCES:

Parker, Roland, Town and Gown, the 700 Years War in Cambridge, Patrick Stephens, Cambridge, 1983

Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space, tr. D Nicholson-Smith, Blackwell Publishing, 1991

Cooper, Charles Henry, volume 1, Annals of Cambridge, Cambridge, 1842

Cooper, Charles Henry, volume 2, Annals of Cambridge, Cambridge, 1843